13.04 - 31.05.2025

Curated by Justine Do Espirito Santo

• Version française

• Press release

Why are we drawn to the strange? What is it about being unsettled, haunted, or even outright disturbed that keeps pulling us back? From horror films, true crime and sci-fi to gothic novels, there’s a vast array of pop culture built around feeding our craving for unease. As these genres only seem to grow in popularity, it’s worth asking: is this simply catharsis, or is something else at play?

Many have theorized the strange and its aesthetics, starting with Freud who in 1919 defined the Uncanny as the realm of the strangely familiar, that which brings us back to something that was once known1.

More recently, Mark Fisher distinguished two main categories of cultural productions concerned with the strange, in The Weird and the Eerie2. The Weird is that which does not belong — a rupture in the familiar, something intruding that shouldn’t be there. The Eerie, meanwhile, is defined by absence and agency, the feeling of something missing that should be present, or something present that shouldn’t have a will of its own. Think of abandoned shopping malls, late-night office buildings, Kubrick’s endless hallways in The Shining — empty, but waiting.

One explanation is that these unsettling narratives offer relief from the mundane. But Fisher goes further, linking the appeal of the weird and the eerie to contemporary capitalism. Capitalism is eerie, he says: it doesn’t physically exist, yet it shapes the world, generating systemic violence, warping reality in ways we struggle to comprehend. The horror isn’t just in ghost stories but in the slow disintegration of public institutions, in the creeping disappearance of structures meant to keep us safe — education, healthcare, stability itself.

Maybe that’s why the 20th and 21st centuries have only deepened this obsession with the unsettling. We live in an era of real-time trauma, exposed to an endless stream of suffering, from historical atrocities to today’s banal yet horrifying news cycle. No wonder our cultural output reflects a world slipping further into the unknown. But these dark tales aren’t just mirrors of our fears — they’re also projections of something else. A desire for rupture, for something new. The weird and the eerie aren’t just disturbances; they are also invitations to imagine differently, to invent new modes of existing.

Random Access Memory explores the aesthetics of the unsettling and its transgressive potential in the works of Tom Allen, Brice Dellsperger, Trisha Donnelly, Pati Hill, Ingrid Luche, Bruno Pelassy, and Torbjørn Rødland.

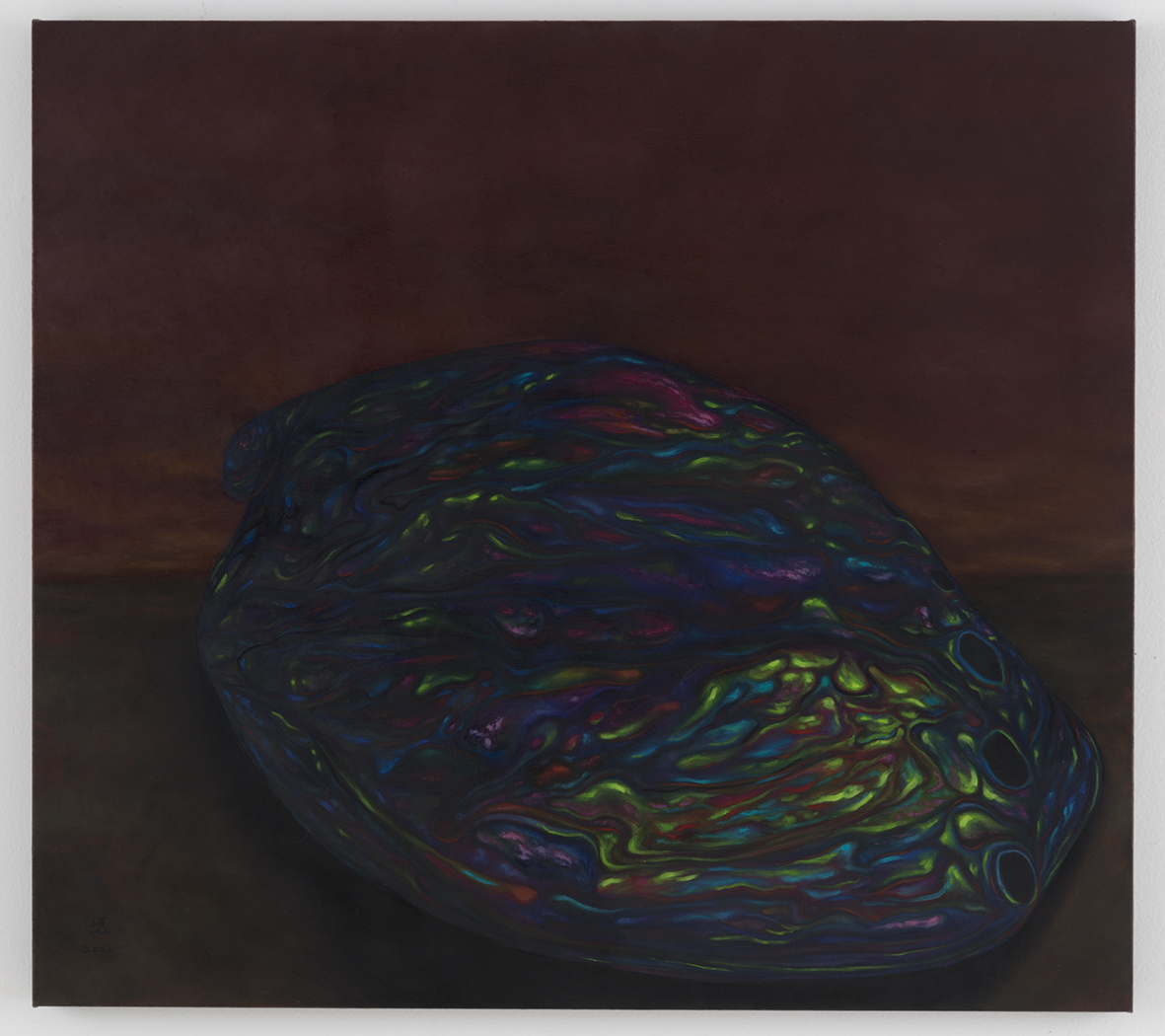

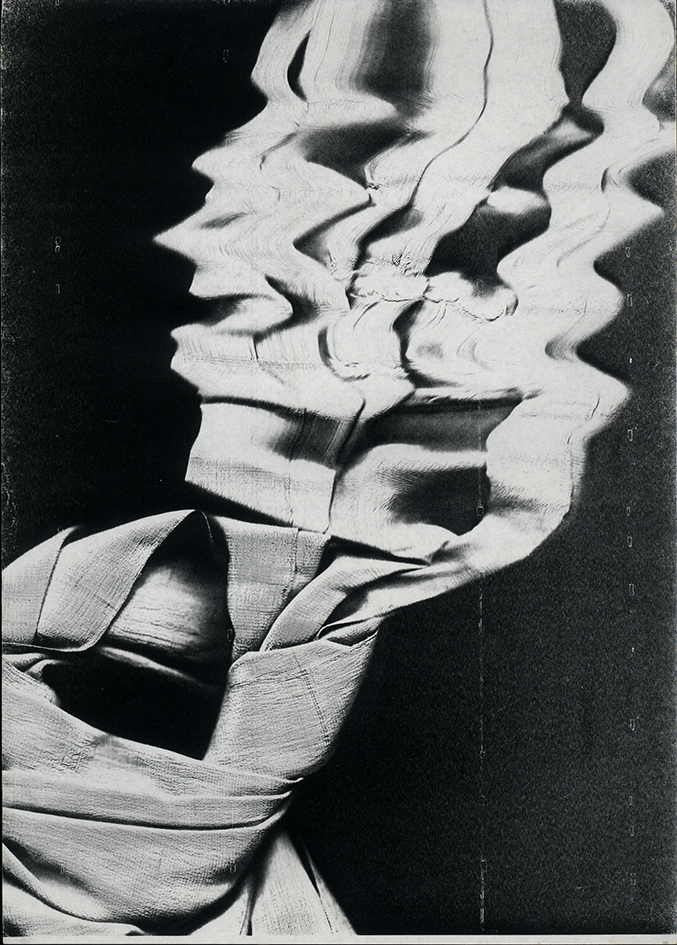

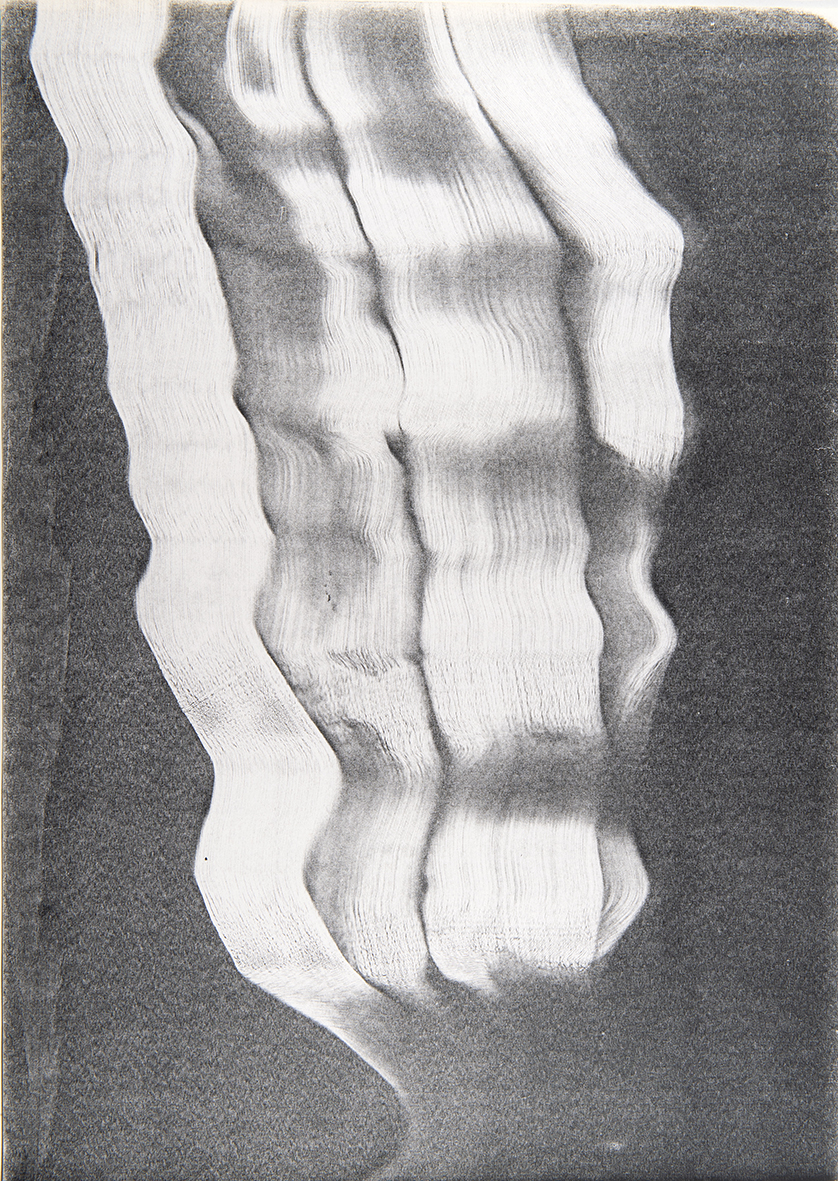

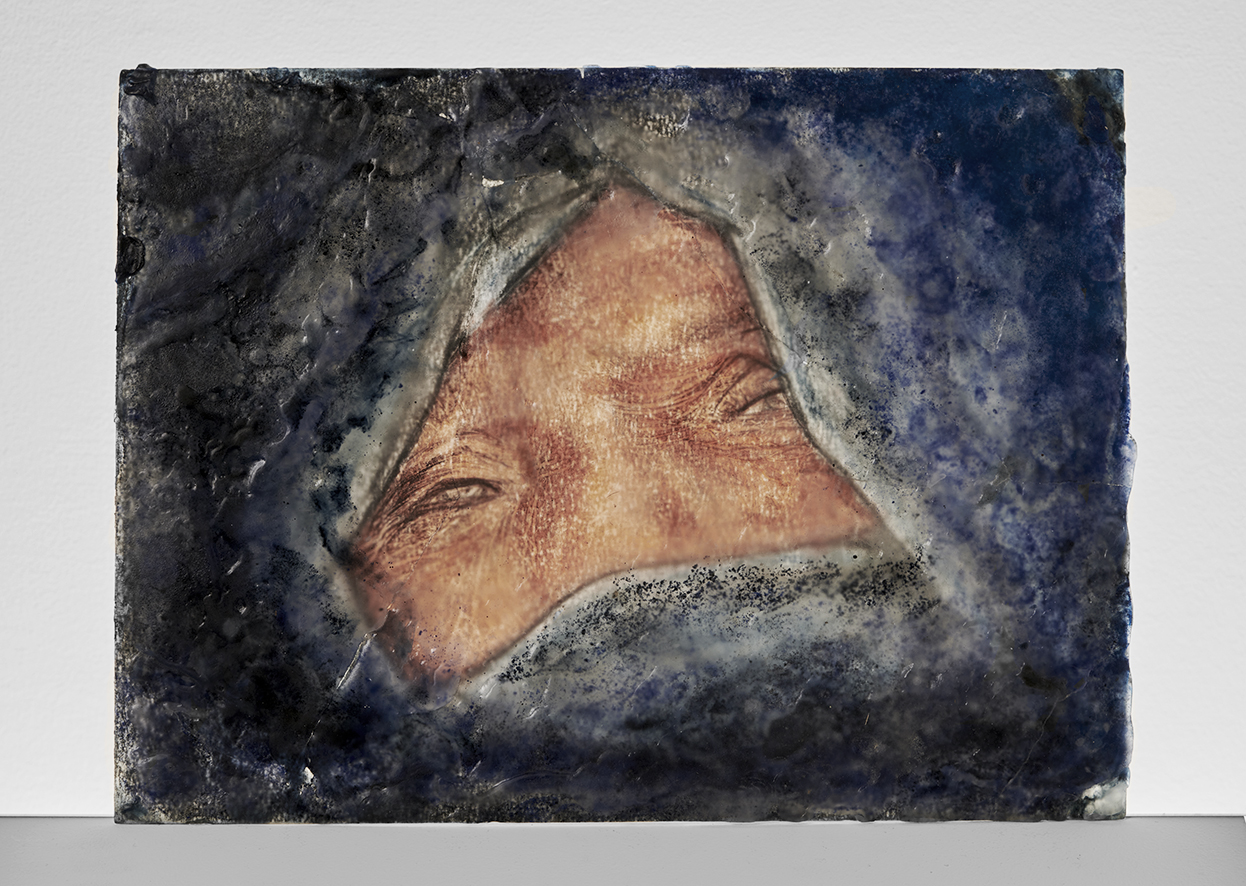

In a disturbing play with scale, Tom Allen’s Polished Shell appears oversized, dwarfing the landscape behind it and evoking an alien-like creature. Similarly, Trisha Donnelly’s blown-out tracings of the cracks left by a termite suggest the hidden presence of much bigger parasite. Brice Dellsperger’s pastiche of Brian de Palma’s The Black Dahlia in Body Double 23 collapses notions of identity and fiction through glitches, refracting reality. Pati Hill’s Xerographs and Bruno Pelassy’s drawings on wax exude a spectral quality, gesturing towards the ghostly imprints of past lives. Ingrid Luche’s 060919-1510 Forest Knoll films the exterior of an empty house with the cold, mechanical gaze of surveillance, turning absence into a main character. Finally, Torbjørn Rødland disturbs seemingly pristine, magazine-ready images by inserting situations of discomfort and ambiguous intent.

Through shifts in perception and subversions of identity and space, the artists in Random Access Memory tap into the pervasive alienation that defines our time. But within their distortions, there’s also the potential for something else: an opening, a fracture, an invitation to step beyond the frame.

— Justine Do Espirito Santo

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

© Photo Pauline Assathiany

Pourquoi sommes-nous attirés par l’étrange ? Qu’y a-t-il dans le fait d’être troublé, hanté, voire profondément perturbé, qui nous ramène sans cesse à cela ? Des films d’horreur, du true crime et de la science-fiction aux romans gothiques, la culture populaire regorge d’œuvres nourrissant notre soif d’inquiétante étrangeté. Alors que ces genres ne cessent de gagner en popularité, il vaut la peine de se demander : s’agit-il simplement d’une catharsis, ou y a-t-il autre chose en jeu ?

Nombreux sont ceux qui ont théorisé l’étrange et son esthétique, à commencer par Freud, qui définissait en 1919 l’inquiétante étrangeté (the Uncanny) comme le domaine du familier devenu étrange, ce qui nous ramène à quelque chose que nous avons autrefois connu.

Plus récemment, Mark Fisher a distingué deux grandes catégories de productions culturelles liées à l’étrange dans The Weird and the Eerie2. Le Bizarre (the Weird) est ce qui ne devrait pas être là—une rupture dans le familier, une intrusion anormale. L’Étrange (the Eerie), quant à lui, est défini par l’absence et l’agentivité, la sensation qu’il manque quelque chose qui devrait être présent, ou qu’il y a une présence qui ne devrait pas avoir de volonté propre. Pensez aux centres commerciaux abandonnés, aux immeubles de bureaux la nuit, aux couloirs sans fin dans The Shining de Kubrick—vides, mais en attente.

C’est peut-être pourquoi les 20e et 21e siècles n’ont fait qu’approfondir cette obsession pour le troublant. Nous vivons à l’ère du traumatisme en temps réel, exposés à un flot incessant de souffrance, des atrocités historiques aux actualités quotidiennes, banales et pourtant terrifiantes. Il n’est donc pas surprenant que notre production culturelle reflète un monde qui glisse toujours plus loin dans l’inconnu. Mais ces récits sombres ne sont pas seulement les miroirs de nos peurs—ils sont aussi les manifestations d’autre chose. Un désir de rupture, d’émergence du nouveau. L’étrange et l’inquiétant ne sont pas de simples perturbations ; ce sont aussi des invitations à imaginer autrement, à inventer de nouvelles façons d’exister.

Random Access Memory explore l’esthétique de l’inquiétant et son potentiel transgressif à travers les œuvres de Tom Allen, Brice Dellsperger, Trisha Donnelly, Pati Hill, Ingrid Luche, Bruno Pelassy et Torbjørn Rødland.

Dans un jeu troublant d’échelle, Polished Shell de Tom Allen apparaît gigantesque, écrasant le paysage en arrière- plan et évoquant une créature extraterrestre. De même, les empreintes agrandies des fissures laissées par des termites qui figurent dans les photos de Trisha Donnelly suggèrent la présence cachée d’un parasite bien plus grand. Le pastiche du Dahlia Noir de Brian De Palma par Brice Dellsperger dans Body Double 23 déconstruit les notions d’identité et de fiction à travers des glitchs, réfractant ainsi la réalité. Les xerographes de Pati Hill ainsi que les dessins enduits de cire de Bruno Pelassy dégagent une qualité spectrale, évoquant les empreintes fantomatiques de vies passées. 060919-1510 Forest Knoll d’Ingrid Luche filme l’extérieur d’une maison vide avec le regard froid et mécanique de la surveillance, transformant l’absence en un personnage principal. Enfin, Torbjørn Rødland trouble des images apparemment impeccables aux apparences de magazines de mode en y insérant des situations évoquant un malaise et des intentions ambiguës.

À travers des jeux de perception et de subversion de l’identité et de l’espace, les artistes de Random Access Memory captent l’aliénation omniprésente qui définit notre époque. Mais dans ces distorsions, il y a aussi le potentiel d’autre chose : une ouverture, une fracture, une invitation à franchir les limites du cadre.

— Justine Do Espirito Santo

Tom Allen, Polished Shell, 2012. Oil on canvas. 66 x 74 cm. Unique. Photo: © Marc Domage

Brice Dellsperger, Body Double 23, 2007. Video, SD/VHS to digital Betacam, color, sound and framed lighjet c-print. 7 min. 28 sec. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Photo: All rights reserved

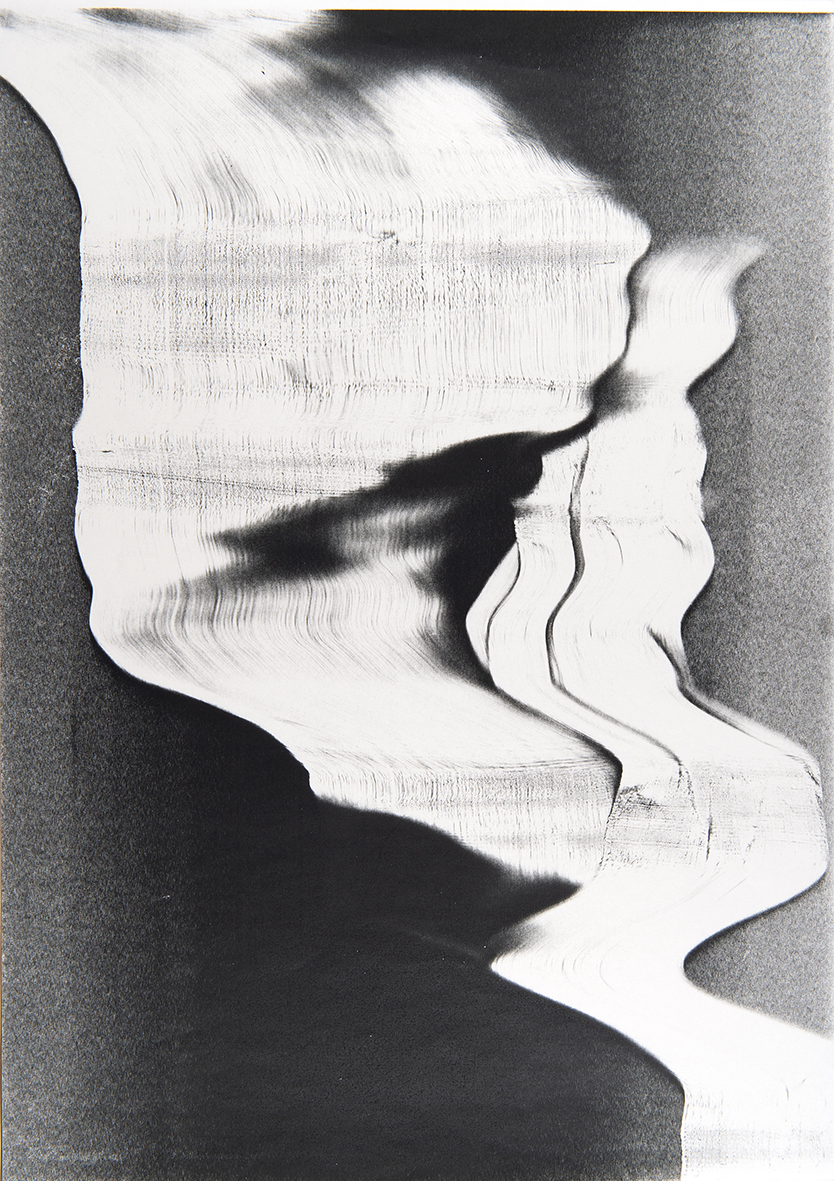

Pati Hill, Untitled (scarf), 1983. Xerograph. 43,3 x 31 cm. Unique. Photo: All rights reserved

Pati Hill, Untitled (scarf), 1983. Xerograph. 43,3 x 31 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

Pati Hill, Untitled (scarf), 1983. Xerograph. 43,3 x 31 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

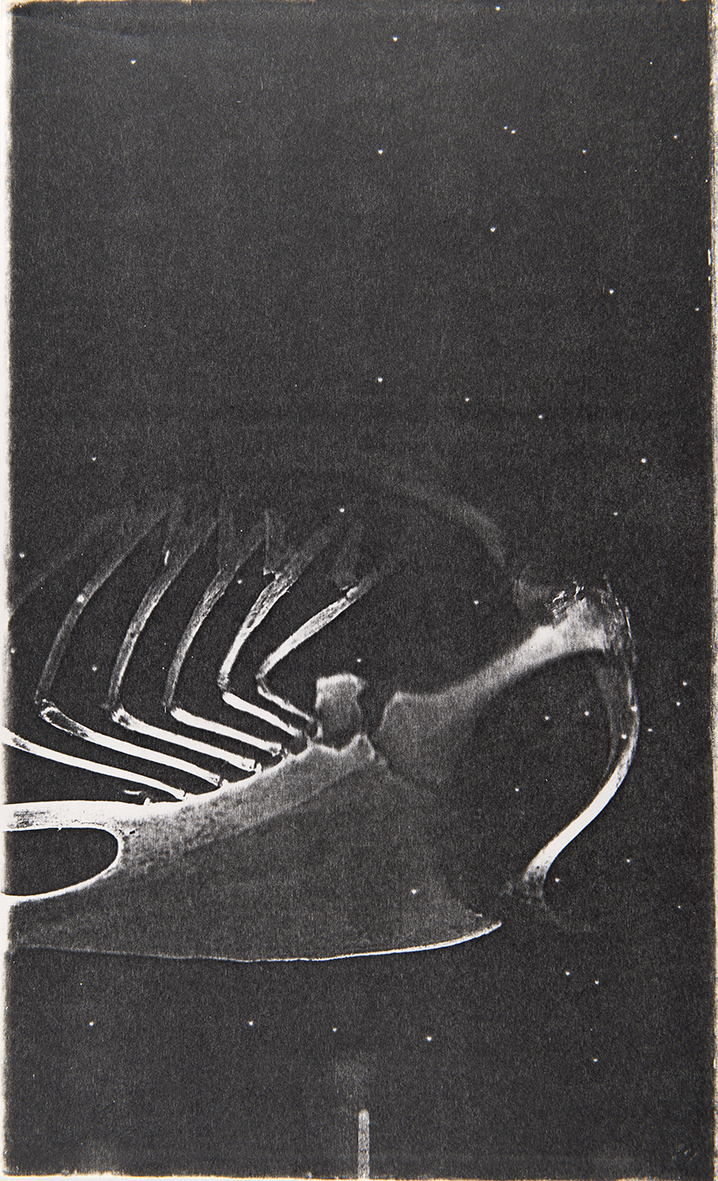

Pati Hill, Untitled (Swan's bone), 1978. Xerograph. 36,8 x 22,9 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

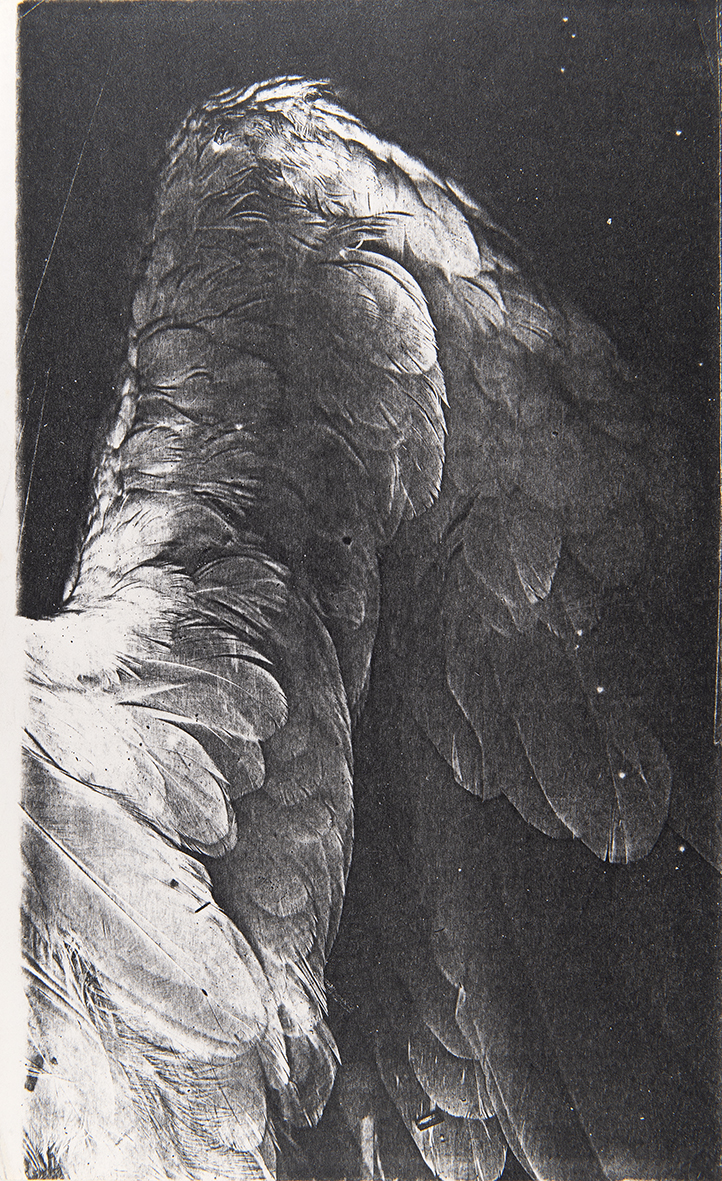

Pati Hill, Untitled (Swan's wing), 1978. Xerograph. 36,8 x 22,9 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

Pati Hill, Untitled (Swan's wing), 1978. Xerograph. 36,8 x 22,9 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

Pati Hill, Untitled (Swan's feathers), 1978. Xerograph. 36,8 x 22,9 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage

Ingrid Luche, Chinoiserie (Feu de cheminée), 2014. Paint, ink and glazing on laquer finish particleboard. 80 x 120 x 2,5 cm . Unique. Photo: © Marc Domage

Ingrid Luche, 060919-1510 Forest Knoll, 2008. Video, colour, sound. 2 min. 18 sec. Photo: All rights reserved.

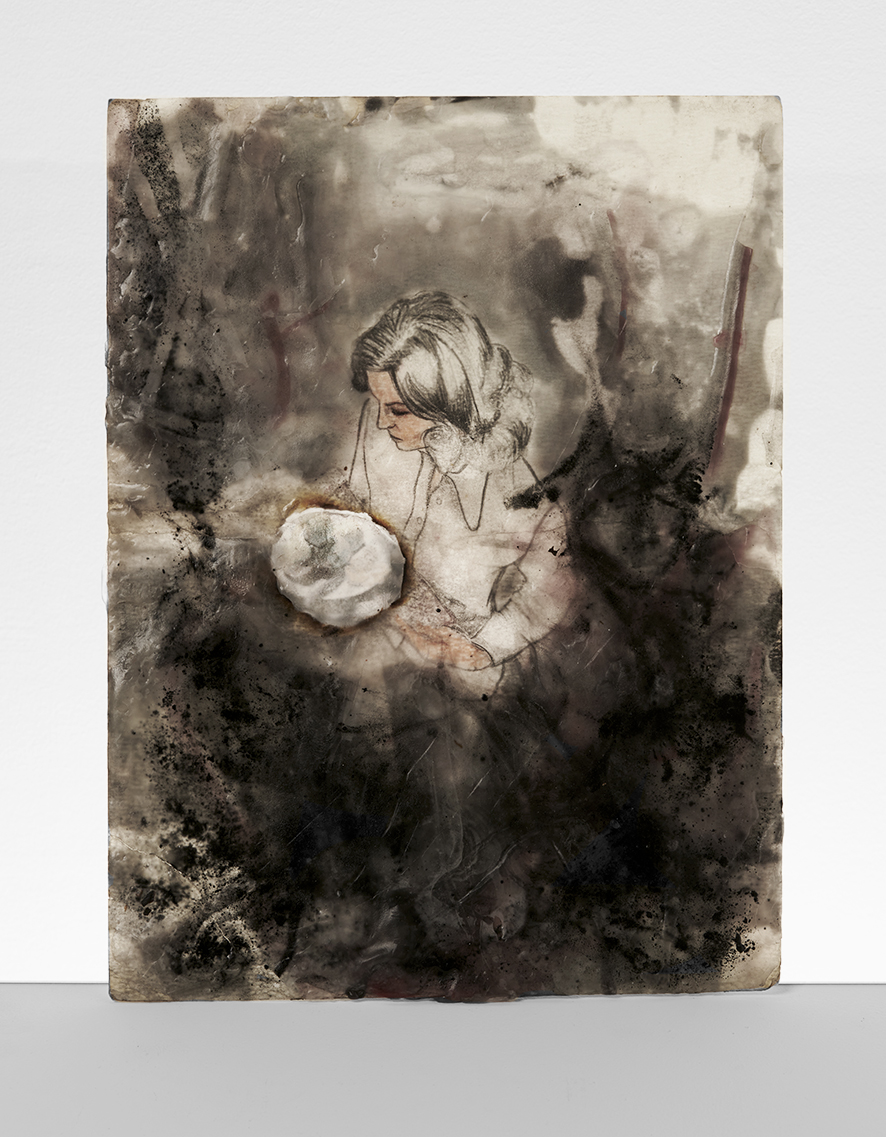

Bruno Pélassy, Sans titre, 1996. Pencil on paper, paraffin wax, pigment. 32 x 24 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage.

Bruno Pélassy, Sans titre, 1996. Pencil on paper, paraffin wax, pigment. 32 x 24 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage.

Bruno Pélassy, Sans titre, 1996. Pencil on paper, paraffin wax, pigment. 24 x 32 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage.

Bruno Pélassy, Sans titre, 1996. Pencil on paper, paraffin wax, pigment. 24 x 32 cm. Unique. Photo: Marc Domage.

Torbjørn Rødland, 5w4, 2015-2017. Framed chromogenic print on Kodak Endura paper. 106,7 x 84,6 cm. Edition of 3 + 1 AP. Photo: Marc Domage.

Torbjørn Rødland, Ace of Cups, 2017. Chromogenic print, Kodak Endura paper. 107 x 82 cm. Edition of 3 + 1 AP. Photo: Marc Domage.

Torbjørn Rødland, Head and Fingers, 2019-2022. Chromogenic print, Kodak Endura paper. 62,5 x 78,5 cm. Edition of 3 + 1 AP. Photo: Marc Domage.

Trisha Donnelly, Untitled, 2005. 4 c-prints (printed by the artist). Variable dimensions: 246 x 106,5 cm, 265 x 106,5 cm, 268 x 106,5 cm, 250 x 106,5 cm. Unique. Photo: Pauline Assathiany.