• English version

• Press release

LE MONDE

(1) C’est l’exposition d’art « Américain Latin » organisée au Musée Galliera. Avant 1924, comme l’explique Michele Greet dans son article « Occupying Paris: The First Survey Exhibition of Latin American Art », des expositions s’étaient concentrées sur des artistes individuels ou des tendances nationales. Il s’agit ici de la naissance d’un nouveau modèle d’exposition présentant des artistes de divers pays de la région latino-américaine, privilégiant la provenance géopolitique des œuvres au détriment de leur cohérence stylistique. Se posait donc la question de l’existence ou de la possibilité de l’existence d’une « esthétique latino-américaine » distincte à celle de l’art européen.

THE WORLD

Un homme du village de Neguá, sur la côte de Colombie, parvint à monter au ciel. À son retour, il raconta. Il dit comment, de là-haut, il avait contemplé la vie humaine. Il dit que nous sommes une mer de petites flammes.

—Ç’est ça le monde—révéla-t-il—une foule de gens, une mer de petites flammes.

Chaque personne brille de sa propre lumière au milieu de toutes les autres. Il n’y a pas deux flammes identiques. Il y a de grandes flammes et de toutes petites flammes, et des flammes de toutes les couleurs. Il y a des gens à la flamme sereine qui ne se préoccupe pas du vent, et des gens à la flamme folle qui emplit l’air d’étincelles. Quelques flammes, balourdes, n’éclairent ni ne brûlent ; mais d’autres embrasent la vie d’un désir si intense qu’on ne peut les regarder sans cligner des yeux, et, si on s’en approche, on s’enflamme.

Eduardo Galeano, 1989

Traduit par Pierre Guillaumin

***

Il y a un siècle, en 1924, la première exposition d’art de l’Amérique Latine a eu lieu à Paris (1). C’était l’entre-deux-guerres, plus de 300 artistes latino-américains sont arrivés dans la Ville Lumière et de la fureur des années folles ont éclos des premières communautés. La plupart de ces artistes se côtoyaient quotidiennement pour la première fois : ils fréquentaient des académies libres, partagaient des ateliers communs, organisaient et participaient à des expositions, échangaient dans les cafés et les terrasses parisiennes… Relégués à la catégorie « d’autre », soumis à une nouvellement découverte identité qui leur avait été imposé et dont Paris est devenu la capitale (2) , les artistes latino-américains naviguaient la scène française en essayant de s’affranchir ou, au contraire, en apaisant les attentes stéréotypées exotisantes du public européen.

Que subsiste-t-il de la présence latino-américaine à Paris ? Une communauté artistique latino-américaine peut-elle exister aujourd’hui ? Sous quelle forme ?

Pour tenter de répondre à ses interrogations, l’exposition se rapproche à la figure et l’œuvre littéraire d’Eduardo Galeano, grand auteur de la question latino-américaine, dont l’encore obscur Livre des Étreintes (1989), atteste d’une expérimentation stylistique tout à fait originale. Loin d’être tissé, comme c’est habituellement le cas dans les autres ouvrages de l’auteur, d’un discours continu du début à la fin, le livre est composé de paragraphes courts et disperses, sans presque aucun fil conducteur de l’un à l’autre. Il s’agit plutôt d’idées et de réflexions sur des sujets divers, allant des problèmes métaphysiques de l’être, du monde et du langage, aux rêves et aux souvenirs personnels de l’auteur. À l’image d’une histoire latino-américaine perçue comme une « réalité déconnectée, brisée, fragmentée » (3), Galeano emploie la fragmentation, non comme un renoncement à la totalité mais plutôt comme une tentative de créer une conscience plurielle, plurivoque (4). L’exposition fait écho à cette construction littéraire singulière en n’imposant aucun cadre thématique préalable et s’éloignant de toute volonté d’homogénéisation identitaire afin de célébrer la diversité d’identités en concomitance à Paris. Une communauté peut bien exister sans pour autant nier l’individualité des membres qui la conforme.

Comme le suggère son titre, le Livre des Étreintes est parsemé de micro-contes sur le rapprochement physique et émotionnel entre individus et, plus largement, sur « l’amoureuse notion de collectivité » (5). Galeano dénonce l’étroite liaison entre le capitalisme et la désarticulation et l’affaiblissement des valeurs communautaires qui en découlent. Selon lui, « l’individualisme est le grand dynamiseur du marché » (6) alors que « la communauté est la tradition la plus ancienne des Amériques, la plus américaine de toutes » (7). Revenant à cette origine, l’exposition est le résultat d’un processus collectif déclenché par l’invitation du commissaire à un premier artiste qui à subséquemment fait appel à un homologue qui lui est proche et ainsi de suite.

L’hétéroclite collection d’œuvres présentée à cette occasion n’est pas censée proposer un commentaire didactique sur des thématiques si fréquemment associées à l’art de l’Amérique Latine comme le militantisme politique, la mythologie ou l’imaginaire précolombien, l’immigration ou l’exil, mais plutôt révéler l’existence d’un réseau bâti sur la pérennité et la solidité de l’amitié et de l’amour. Par le biais de signes et de fragments, d’une sémantique et d’une palette réduite, l’exposition privilégie le récit personnel ainsi que l’analyse et l’observation de l’environnement immédiat qui est lyriquement exalté puis transfiguré en proposition poétique par l’artiste.

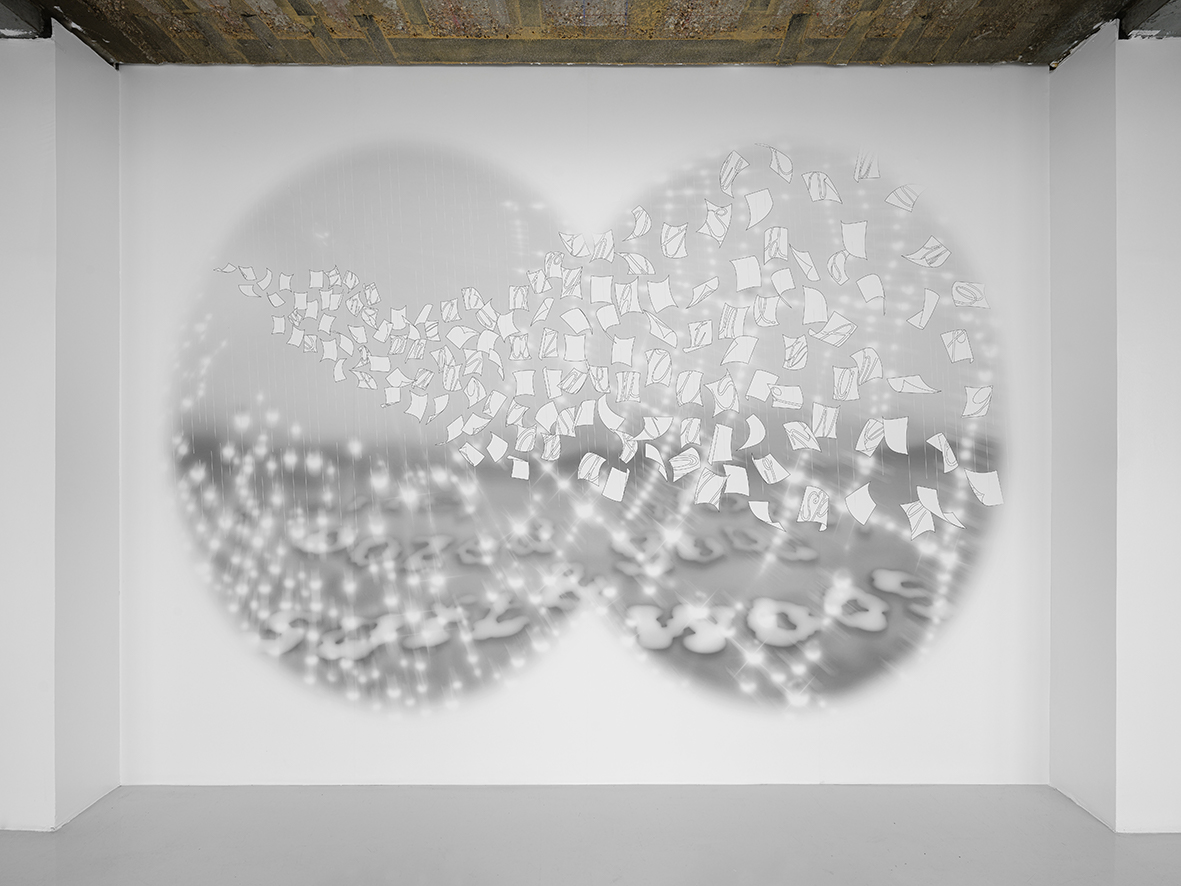

L’exposition est construite à l’image du monde conçu par Galeano où les artistes, petites flammes uniques, ont embraser mutuellement leurs vies d’un intense désir en espérant que le spectateur s’approche et s’enflamme à son tour.

***

(2) Greet mentionne notamment l’enthousiasme de l’intellectuel brésilien Pedro Osorio qui, non sans arrière-pensées politiques, proposait que Paris devienne la capitale culturelle de l’Amérique Latine, un terrain fertile où devait s’épanouir un “cerveau latino-américain” partagé par tous les membres de la communauté artistique.

(3) Galeano, Eduardo cité dans González, José Ramón, « La estrategia del fragmento : El Libro de los Abrazos de Eduardo Galeano », Castilla: Estudios De Literatura, n° 23, 1998, p. 106

(4) Ibid.

(5) De Assis Augusto, Ailton Magela & Zimbrão Da Silva, Teresinha Vânia, « Gestos amorosos en la escritura de Eduardo Galeano », VI Congreso Internacional De Literatura, Estética Y Teología, El Amado En El Amante : Figuras, Textos Y Estilos Del Amor Hecho Historia, 17-19, Mai 2016

(6) Galeano, Eduardo cité dans Prádanos, Luis, « Ecocrítica Y Epistemología Subalterna En Eduardo Galeano », Revista Canadiense De Estudios Hispánicos, 2012, p. 344

(7) Ibid.

A man from the town of Neguá, on the coast of Colombia, was able to climb to high heaven. On his return he told the story. He said he had contemplated human life from above. And he said we are a sea of little fires.

—The world is just that —he revealed—, a bunch of people, a sea of little fires.

Each person shines with his own light among all the others. No two fires are the same. There are big fires and small fires and fires of all colors. There are people of serene fire, who don’t even notice the wind, and people of crazy fire who fill the air with sparks. Some fires, silly fires, do not light or burn; but others burn the life with such passion that one cannot look at them without blinking, and whoever comes close to them lights up.

Eduardo Galeano, 1989

***

A century ago, in 1924, the first Latin American art exhibition was held in Paris (1). It was the inter-war years, over 300 Latin American artists landed in the City of Light, and out of the frenzy of the Roaring Twenties sprang the first communities. Most of these artists were meeting on a daily basis for the first time: they attended free academies, shared studios, organized and participated in exhibitions, exchanged ideas in Parisian cafés and terraces... Relegated to the category of «other», subjected to a newly discovered identity that had been imposed on them and of which Paris had become the capital (2), Latin American artists navigated the French scene, trying to disengage themselves or, on the contrary, appeasing the exoticizing stereotypical expectations of European audiences.

What remains of the city’s Latin American presence? Can a Latin American artistic community exist today? And under what form?

To attempt to answer these questions, the exhibition turns to the figure and literary work of Eduardo Galeano, the great author of the Latin American question, whose still obscure Book of Embraces (1989), displays a highly original stylistic experimentation. Far from being woven, as is usually the case in the author’s other works, of a continuous discourse from beginning to end, the book is made up of short, scattered paragraphs, with almost no thread running from one to the next. Instead, they are ideas and reflections on a variety of subjects, ranging from metaphysical problems of being, the world and language, to the author’s personal dreams and memories. In the image of a Latin American history perceived as a «disconnected, broken, fragmented reality» (3), Galeano employs fragmentation, not as a renunciation of wholeness, but rather as an attempt to create a plural, plurivocal consciousness (4). The exhibition echoes this singular literary structure, imposing no prior thematic framework and eschewing any desire to homogenize identity in order to celebrate the diversity of converging identities in Paris. A community can exist without denying the individuality of its members.

As its title suggests, the Book of Embraces is interspersed with micro-tales about the physical and emotional bonding of individuals and, more broadly, about «the loving notion of collectivity» (5). Galeano denounces the close relationship between capitalism and the resulting disintegration of community values. According to him, «individualism is the great driving force of the market» (6), whereas «community is the oldest tradition in the Americas, the most American of all» (7). Returning to this origin, the exhibition is the result of a collective process triggered by the curator’s invitation of a first artist, who in turn called upon a peer, and so on.

The eclectic collection of works presented on this occasion is not intended to offer a didactic commentary on themes so frequently associated with Latin American art, such as political activism, pre-Columbian mythology or imaginary, immigration or exile, but rather to reveal the existence of a network built on the durability and solidity of friendship and love. Through the use of signs and fragments, a reduced vocabulary and palette, the exhibition privileges the personal narrative as well as the analysis and observation of the immediate surrounding environment, which is lyrically exalted and ultimately transfigured into a poetic proposition by the artist.

The exhibition is shaped according to the image of the world conceived by Galeano, where the artists, unique little flames, have set each other’s lives ablaze with intense desire, hoping that the viewer will approach their work and catch fire themselves.

***

(1) This is the «Exposition d’Art Américain Latin» held at the Musée Galliera. Prior to 1924, as Michele Greet explains in her article «Occupying Paris: The First Survey Exhibition of Latin American Art», exhibitions had focused on individual artists or national trends. This was the birth of a new exhibition model, presenting artists from various countries in the Latin American region, and emphasizing the geopolitical provenance of the works rather than their stylistic unity. This raised the question of the existence or possibility of a «Latin American aesthetic» distinct from that of European art.

(2) Greet mentions in particular the enthusiasm of the Brazilian intellectual Pedro Osorio, who, not without political ulterior motives, suggested that Paris should become the cultural capital of Latin America, a fertile breeding ground for a «Latin American brain» shared by all members of the artistic community.

(3) Galeano, Eduardo quoted in González, José Ramón, « La estrategia del fragmento : El Libro de los Abrazos de Eduardo Galeano », Castilla: Estudios De Literatura, n° 23, 1998, p. 106

(4) Ibid.

(5) De Assis Augusto, Ailton Magela & Zimbrão Da Silva, Teresinha Vânia, « Gestos amorosos en la escritura de Eduardo Galeano », VI Congreso Internacional De Literatura, Estética Y Teología, El Amado En El Amante : Figuras, Textos Y Estilos Del Amor Hecho Historia, 17-19, Mai 2016

(6) Galeano, Eduardo quoted in Prádanos, Luis, « Ecocrítica Y Epistemología Subalterna En Eduardo Galeano », Revista Canadiense De Estudios Hispánicos, 2012, p. 344

(7) Ibid.

IRENE ABELLO

FACUNDO CERAIN VAZQUEZ

FERNANDA MORGAN

LÍNEA RECTA

CARMEN ALVES

JOSHUA MERCHAN RODRIGUEZ

ISADORA SOARES BELLETTI

DANIELA STUBBS-LEVÍ