Entretien pour Gilles Dusein / Conversation for Gilles Dusein

*******

Olivier Pierre Jozef and Florence Bonnefous, conversation about THE "Tattoo Collection" exhibition, for the fanzine Agent Double #1, 2014

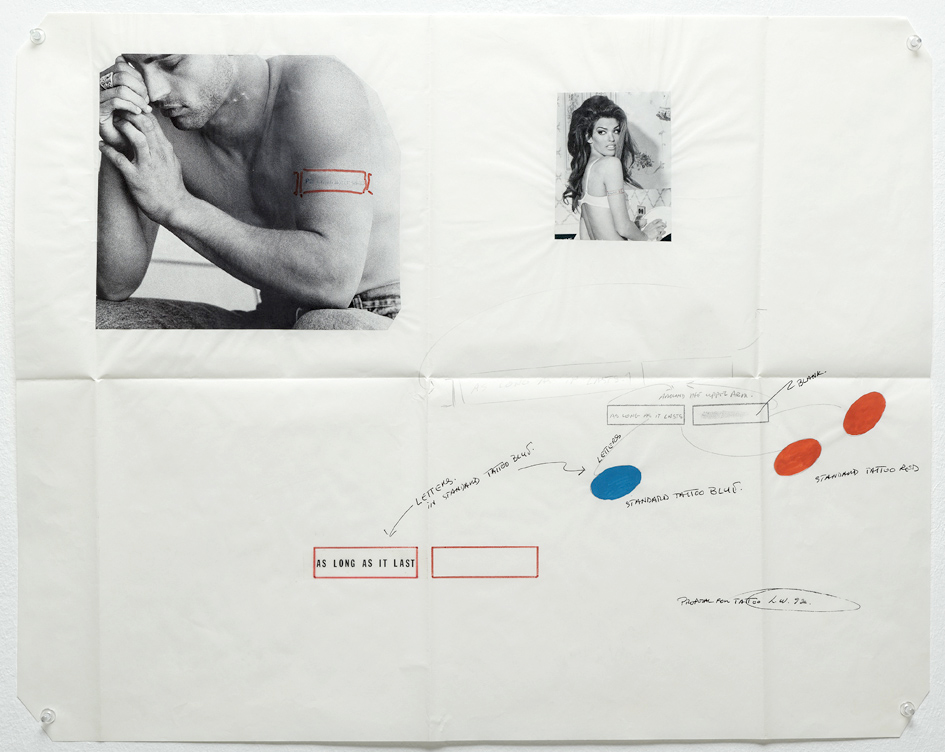

For Gilles Dusein OPJ: Florence, could you tell us something about the initial Air de Paris project? How did the gallery come about? F: A bit by chance, actually. I met Édouard Merino in 1989, when we were doing a postgrad course in contemporary art mediation at Le Magasin, the centre for contemporary art in Grenoble. We'd both been selected by Jacques Guillot, founder of Le Magasin and of this course called "L'École" (School) – the equivalent at the time was the Whitney Program in New York. Édouard and I got along well and at the end of the academic year the two of us decided to put together a project: this boiled down to opening a gallery – we couldn't really see any other possibilities – so we opened a space in Nice. OPJ: Nice straight off? Why Nice? F: First of all we'd gone looking in Paris. We found a place and the day before we were due to sign the lease and hand over the deposit, we had a dinner to celebrate; by the end of the dinner we'd decided to move away from the centre and be more on the outskirts. And what better outskirts were there than the coast? Things were made easier by the fact that Édouard's parents live in Monaco and we could stay with them until we found somewhere in Nice. OPJ: Wasn't the gallery called Air de Paris from the start? Is there a particular reference there? F: That's right, it was called Air de Paris from the outset – an allusion to Duchamp, of course. But there was a play on words as well: pari in French is a bet, and this was going to be a place – an aire – where you could bet on the future. OPJ: The gallery opened in 1990 and the "Tattoo Collection" project was born a year later. How did that happen? F: Chance again – things setting up a ripple effect. When we were at Le Magasin we'd met Lawrence Weiner and got along really well with him. Then one day – one night actually – I was thinking about tattooing in relation to his statement that a work of art could be executed or not, to sum up his approach a bit roughly. Weiner and his lifelong companion Alice both wear tattooed wedding rings. Initially I was thinking of something non-permanent and asked him for an edition of decals – temporary tattoos. He told me he loved my idea and that my intuition of the connection with what governed his entire oeuvre was right on the mark. On the other hand he thought a temporary tattoo was a half-measure; instead he proposed a tattoo project – on condition that I have myself tattooed. So I had his project tattooed on my back: 1/2 Way To Heaven (&) Vers Les Étoiles*, drawn Weiner-style with typographical signs and stars. The star is one of the earliest tattoos there is, a marker and a good-luck charm worn by sailors following the morning star. My tattoo was done the day we launched a project by Weiner on the roof of a building in Monaco: the first chapter of our Project for UFO, a series of exhibitions which, unless people were brought by appointment to the roof of this building – one of the tallest in Monaco – "could only be seen by extra-terrestrials." So there I was, during this vernissage, on a roof, looking out to sea and the horizon with this work of art on my back. And as I moved about I could feel my verticality at the centre of Weiner's new work: a statement in English plus its French translation painted on the low wall surrounding this vast terrace, this spreading horizontal plane. At that moment I was seized by an acute awareness of the impermanence of the body, and this set me thinking about the meaning of a work of art. How does the body contribute to the conveying and the appreciation of a work of art? That was the week when the idea came together for inviting artists to suggest tattoo projects. We got it underway very simply, by contacting thirty or so artists; I don't recall who the core participants were, but each of them was asked to invite other people. Things jelled pretty fast and spread like wildfire to the United States, a bit like a mail art venture, as we had no money at all and scarcely any other resources. Letters with tattoo projects started pouring in, together with all sorts of comments from people who found the idea of an exhibition really exciting. We got mail from people who were already really well known, like John Baldessari, Vito Acconci and Richard Prince, and two great new projects from Lawrence Weiner. As well as from people who were totally unknown at the time, but made their reputations later on, and lots who've since vanished – either fallen into oblivion or lost to us forever, in some cases because of AIDS-related complications. In fact the project came to involve a major, very poignant issue of the period: the impermanence of the body, and all the social implications of the AIDS epidemic – the segregation and exclusion of HIV-positive people, and the denial of the problem. At the time, in the early 90s, nobody knew exactly what the virus was; it had been identified at least five years earlier, but there were still all kinds of rumours circulating. I'd already lost a woman friend in Strasbourg around 1983, and I recall some people keeping away from me because I was visiting her in hospital and they were afraid of being infected. So we were accumulating stuff as we went along and we realised the proportions the project was taking on and how far it was taking us beyond the original idea. That was when I drew up a kind of questionnaire, an "artwork form" attempting to clarify "what exactly it was that we were receiving". Was the drawing the work, or the actual tattoo, or both? And given that it was all happening via a private gallery, could the project be sold? Could a price be put on it? The art market of the time was less developed than it is now; it was a far cry from the rampant reification of the last 20 years, but the situation did already relate to issues of reification and the commodification of bodies. When I say that, I'm not talking about prostitution, but about bodies turned into carriers of advertising and brand names; about the bodies of human beings as exchangeable products within a huge free-market structure that was in the process of globalisation – even if the term was still little used at the time. The questionnaire tried, neutrally and with no curatorial emphasis, to put simple questions and see what would emerge. We didn't make much use of the results, which are now in our archives, although they were readily available during the exhibitions. We undertook this project with a close friend who just has to be mentioned here and to whom I've dedicated this text. His name was Gilles Dusein and he ran the Urbi et Orbi gallery in Paris. I'm speaking in the past tense because he's since died of AIDS. He was one of the first people I talked to about the project, by the pool at the La Pérouse hotel in Nice, where he often stayed. He was enthusiastic; straight away he wanted to be directly involved and even before the first exhibition opened he had a work by Philippe Perrin tattooed on his chest: a black Beretta pistol, with the "Star Killer" signature Perrin was using at the time. Later Gilles acquired another Lawrence Weiner project, A Malin, Malin & 1/2, and had it tattooed on his biceps. I'm thinking, too, of another one of Weiner's tattoo projects that was really great. An "armband", a tattoo that encircles the biceps and says, in Weiner's characteristic lettering and plain colouring, As long as it lasts. This is a powerful way of stating that the body bearing this work is a much more ephemeral vehicle than a canvas or any other contemporary image carrier; maybe this ties in with the forms taken by performances, when the work as "live" event is ultimately, and simply, replaced by its documentation.