Crime

scene investigator

Murder, suicide, earthquake, arson, car smash... Mexican photographer

Enrique Metinides found humanity in catastrophe, says Adrian Searle

Adrian Searle

Tuesday July 22, 2003

The Guardian

From 1948 until his forced retirement in 1979, the Mexican photographer

Enrique Metinides took thousands of images and followed hundreds of stories

in and around Mexico City. And what images and stories they were: car

wrecks and train derailments, a bi-plane crashed on to a roof, street

stabbings and shootings in the park, apartments and petrol stations set

alight, earthquakes, accidental explosions, suicides, manslaughters, murder.

Metinides photographed his first corpse when he was 12. A year later,

he became an unpaid assistant to the crime photographer of Mexican newspaper

La Prensa, and his pictures appeared in La Nota Roja - the red note or,

more colloquially, the Bloody News, the best-selling tabloid.

Now almost 70, Metinides is about to hold his first European show. He

has said that he based his photographic style on black-and-white action

movies, on cops and gangster flicks. Some of his first boyhood photos

were of what he saw on the cinema screen, while others were of the car

crashes that were always happening outside his father's restaurant. Always

known as El Nino - the boy - Metinides got everywhere from the first,

hanging around the police station, going to the morgue, not chasing the

ambulance but travelling in it as a volunteer with the Red Cross.

Although comparisons with the New York crime-scene photographer Weegee

are inevitable, the context, content and style are quite different. In

their way, Metinides's photos are like scenes from unmade movies, using

a wide-angle lens and daylight flash, the latter in emulation of news

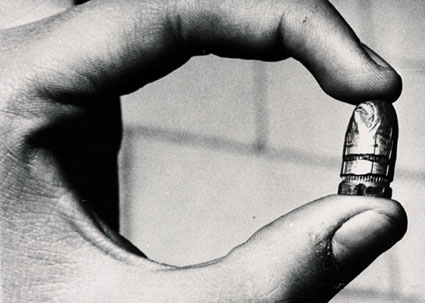

photographers he'd seen in the movies. "My first photograph was always

the facade of the building where the crime has been committed," he

says in an interview in the exhibition's catalogue, "then one of

the entrance, the cartridge case, the blood, the overturned drawer, the

corpse. That's a film but in still photos."

These images aren't cheap magazine "photoplays". The deaths

and disasters are real. Lingering on the blood, the faces of corpses,

a murderer's blood-spattered grin, a stabbing victim's pained astonishment,

Metinides made himself Mexico's best-known newspaper photographer. Images

of such unrelieved and awful intimacy, intensity and apparent salaciousness

are difficult for a British audience, but commonplace in Central and South

America. They occupy a cultural place we find hard to understand.

Metinides doesn't just show us the mutilated and the dead, the bodies

and the blood. He shows us the gathering crowds, the bewildered and transfixed

passers-by, the emergency teams as well as the rubber-neckers. In effect,

he shows us the city and its people, not just the random and cataclysmic

event, but also its effect. He shows us, too, the inexplicable.

Which is not to say in any way that Metinides's photographs are lacking

in humanity. Quite the opposite. They are overflowing with humanity. In

fact, that is the real trouble with them - they show us too much humanity.

In Metinides's images, we don't just see the body dragged out of the water

after the drowning, we see the drowned man underwater, the grey corpse

hovering at the bottom of the swimming pool. Or a body being dragged to

the bank of a river, like some awful bait trawled at the end of a rope,

the spectators on the far bank an inverted frieze reflected in the muddy

water.

We see things we feel we shouldn't be looking at, but it is hard to drag

our eyes away. The dead woman, with her shiny red nails and blonde coiffure,

draped over a mangled post after being hit by a car at a pedestrian crossing,

her made-up face grim in death, just at the moment when the paramedic

is about to cover her with a blanket. The suicide by hanging, dangling

from "the tallest tree in Chapultepec Park, unable to bear the fact

that her husband has taken their daughter to live with him and his lover".

Here, the beautiful tree fills most of the image. The hanged woman is

almost a detail, in the soft dappled light at the foot of the tree.

Metinides's images are sometimes made more unsettling by their evident

aestheticisation, or perhaps rather the way we place them among other

kinds of images, as if to defuse them, render them more acceptable. The

man being brought down from the tangle of power lines on the pole - where

he fried as he tried to illegally tap into the national grid - looks like

an image of Christ's deposition. But aren't paintings and sculptures of

Christ on the cross "aestheticised" too? The sequence of shots

showing two rescuers attempting to approach and grab a would-be suicide

from a stadium gantry (saving him from his wish "to know what death

is like") is also a drama of silhouettes and criss-cross girders

against the white sky as a human event. It is about the spectacle as much

as a lurid, voyeuristic spectacle in itself. In a way, this sequence tells

us why we are looking, as much as it is a record or rescue.

The captions are as terse and direct as the images themselves. They give

us the context, but also leave us baffled: we are, after all, foreigners

here. A woman carries a small box under her arm, as she approaches some

men in business suits on the street. We learn that she is a poor woman

who has been "forced to leave the morgue in order to buy a coffin

for her two-year-old daughter, whose autopsy has been been performed two

hours previously".

Other images are deeply enigmatic in another way. In the background of

one, we see the derailed train at the mouth of a tunnel. In the foreground,

lain on white blankets among the undergrowth is a train worker. Kneeling

at his head, amongst the grasses, a uniformed policeman takes notes. It

is a surreal image. The blanket is like an opened shroud, and the victim

might almost be dreaming. The image is, in fact, like a kind of dream.

The cop could almost be drawing, rather than taking a statement. Everything

is still, almost like a diorama model, and, inadvertantly, beautifully

composed.

So, too, is an incredible photo of a man lying in the street at night,

electrocuted by a fallen power line. There he is, flat out in his suit,

lit only by the luminous flare of the fizzing wire, which also lights

up the curb and silent empty corner. How did Metinides get there, you

ask? Why is there no one else on this otherwise dark and empty street?

The man, we are told, survived.

Perhaps the image that haunts me most shows a late 1940s sedan rolled

on its side in the middle of the road on a bend. If it weren't for the

people, you might think it was a kid's toy, knocked over in a game. A

man stares at the now vertical underside of the car, as if he'd never

seen such a thing before. The car casts a long shadow across the country

highway. Two women cross the road in the low angle of late afternoon light.

One wears a white dress that picks up the sunlight, as does the sleeve

of the man's shirt, the white bodywork and the grinning chrome grille

of the car. You imagine the metal ticking as it cools down and the sound

of crickets and rustling leaves. The women are walking into their own

shadows. The photo has all these white accents: the white dress, the man's

shirt, the white car, the whitewashed roadside markers, the white clouds

massing over distant mountains. Finally, the white unbroken line painted

down the middle of the blacktop, a sweeping cartoon parabola.

It all happened a long time ago, in 1951, somewhere in Puebla State, Mexico.

As far as we can see, no one died. The image has the quality of one of

those memories one is never quite sure was something one experienced oneself,

or was a thing read about and elaborated in the imagination. These photographs

seem to be more the beginning of something than a record of something

past. This is what makes Metinides such a terrific photographer, even

though his subjects are so unrelievedly grim.

Since being ousted from La Prensa, Metinides has not taken a single photograph,

though he hasn't exactly retired. He stays in his Mexico City apartment,

surrounded by TVs and radios, ceaselessly monitoring the bloody news on

the local and satellite channels, videoing second-hand disasters now.

His radios are tuned to the police frequencies, and his shelves are stacked

with video recordings. He has a collection of thousands of toy ambulances,

firetrucks and figures, some arranged in little scenes of rescue and disaster.

He also - curiously - keeps a big collection of plastic frogs. Maybe he

is trying to explain the world to himself. Which is what we do, too, when

we look at these difficult images.

Guardian Unlimited © Guardian Newspapers Limited 2003